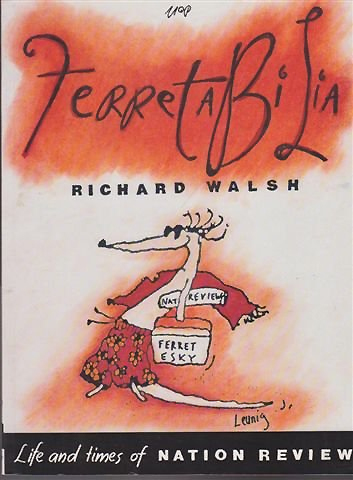

Like a Ferret, lean and nosey

Nation Review was a central part of Australian politics in the early 1970s, and Local Media pioneer Ash Long was there at the beginning.

The weekly Sunday Review newspaper was founded on Sunday, October 11, 1970, and the family of Ash Long (then aged 13) had a part-time newspaper distribution business for Gordon Barton’s Melbourne Sunday Observer.

It would be fair to say that the Long family was a conservative one; Gordon Barton was a left-leaning Liberal, a maverick entrepreneur, with a quite unusual lifestyle for the times. It was an odd combination. Perhaps the unconventional publishing style of the time set a template of fearless, independent reporting that would become the stamo pf Local Media’s newspapers, even half-a-century later.

They were different times. The Menzies-Holt-McMahon-Gorton Liberal Government had been in power in Canberra for several decades. Labor’s Gough Whitlam was to take power two years later, in December 1972.

Long-time Review Publisher Richard Walsh, in his Ferretablia book (University of Queensland Press) reflected in 1993 that the early 1970s had State leaders including Robin Askin (NSW), Joh Bjelke-Peterson (Queensland), Sir Charles Court (Western Australia) and Sir Henry Bolte (Victoria). Only Don Dunstan, South Australia’s flamboyant Premier, broke the mould.

“Harry Miller’s production of Hair had been running for more than a year and Wendy Bacon’s Thorunka was sticking it up the Establishment. The London OZ team was soon to be jailed in grand style, in an upbeat re-run of the prosecution of the OZ boys in Sydney five years previously.

:There were Vietnam marches and moratoria, with Jim Cairns most publicly bearing the standard. There were raids on abortion clinics and the stench of police corruption in the three eastern States was so high even the pollies were finding it difficult to ignore it.”

Michael Cannon, who had briefly edited Gordon Barton’s Sunday Observer in 1969, returned to become ‘Editor-in-Chief’ (there was no Editor) of the Sunday Review. Some of the bylines in the first issue included Sol Encel, Geoffrey Sawer, Cyril Pearl (from Sydney’s Nation), a team from Pete Steedman’s Broadside, and cartoonist Michael Leunig. There were syndication arrangements with the London Spectator and The New Statesman. Included in the team were Bill Green (Assistant Editor) and Richard Beckett (Chief Sub-Editor).

Michael Costigan, former Associate Editor of the Melbourne Roman Catholic weekly, The Advocate, wrote on religious affairs. Other early contributors were Barry Oakley and Niall Brennan.

Richard Walsh, Sydney medical faculty graduate, advertising whiz-kid, POL publisher, had advised Gordon Barton in the 1960s that if the businessman wanted to change public opinion that he should start a newspaper rather than a political party. Barton did both. And in November 1970, Barton offered the Sunday Review’s editorship to Walsh (Cannon having vacated the chair after the fifth issue). Barton offered one-third of Walsh’s advertising agency package to travel from Sydney to Melbourne each week. His first issue was on January 10, 1971.

Walsh remembered: “To house the Sunday Observer Gordon Barton had acquired a disused factory in Melbourne, in the industrial badlands on the banks of the Yarra at what was then best known as the Home of the Holden – Fishermans Bend. Never has there been such a misleadingly enticing suburban name – except perhaps for its neighbour, Garden City. When the Sunday Review was born, it was granted a small corner space in this already cramped set-up.

“The first home of the Sunday Review was thus a pale cream, partly fibro factory that squatted under a tin roof and baked all January in the summer heat. It was totally without windows or charm. The editorial and administration offices were a mean adjunct to the vast barn which housed the Blue Monster, a six-unit Goss. We worked in an atmosphere spiced with the smell of machinery oil, printer’s ink and newsprint.

“Our offices at Lorimer Street, Fishermans Bend, were affectionately known as the Yellow Submarine because of the absence of windows and fresh air. Working there we haqd no sense of day or night; to make our lives almost tolerable Leunig had painted in watercolours a wonderfully bucolic sense of cows grazing in front of a picturesque little farmhouse, framed by checkered curtains and a neatly painted window sill, as though it was in fact a window through which we could gaze out upon an inspiring world of innocently rolling hills. This painting was tacked to the back wall in such a way that each of us could turn to it for blessed relief from the travails of composition.”

Walsh wrote of Mario Sartori, one of the printing crew: “Mario, an amiable and gregarious italian-Australian, doubled as our distribution manager. There was a wonderful story that he was dumping the Sunday Observer’s unsolds (of which there was a preternaturally large number) into the Yarra, across the road from our front door at the river bend where it flowed sluggishly. Beckett held the theory that one day, under riverbed pressure frrom the Observer’s returns, the Yarra would burst its banks and seize the Yellow Submarine in its watery maw.”

Columnist John Hepworth told the story of how the ‘Ferret’ mascot came about: “At the moment of destinby for us Leunig was bent over his desk contentiously drawing (for reasons best knownto himself) the likeness of a dog when Walsh, in relentless pursuit of ideas to promote our public image, passed by and glanced over his shoulder. Any fair-minded man would have recognised the thing Leunig was drawing was at least intended to be a dog, but Walsh has never been hampered by piddling considerations of this sort.

“By God!” he excalimed – a touch of awe, a certain reverence in his voice. “That’s it! That’s exactly what we want! The ferret!”